I was more shocked than delighted when the Vox Book Club voted to read The Epic of Gilgamesh. Why did students at a technical university choose this text – and by a landslide? Sure, I studied Gilgamesh as an undergraduate, but I did Creative Writing at British university, where professors wore tweed and pored over ancient manuscripts. And here were future engineers volunteering to read it, in their spare time?

The Epic of Gilgamesh is an epic poem from ancient Mesopotamia, a historical region of West Asia. Captured on stone tablets, it is the oldest known written story. The age and fragmented nature of the text make it impossible to date the story as a whole. But the “Old Babylonian” version, which is the oldest that survives, is estimated to be from the 18th century BC. It tells of the adventures of King Gilgamesh of Uruk and his companion Enkidu, the wild man.

Nervous about whether the book club would actually enjoy the text, I volunteered to give an introduction at their first meeting. A mini-lecture, if you will. After all, short as it may be, Gilgamesh is a lot more enjoyable when you know what the hell is going on. The students were also nervous. Was I going to talk for an hour? Was I joking when I said there was going to be a quiz? I kept to my twenty-minute time slot on the day, but this article is my revenge. Without further ado, here is my answer to the question: why read The Epic of Gilgamesh?

The World’s Oldest…?

One of the first challenges in discussing this text is how to classify it. Due to its action-packed nature, the scale of the journeys described, and the monster-hunting, it is tempting to think about it as an early fantasy novel. There certainly are similarities, but there are also some key differences.

The novel in its current form is a relatively new genre. Its popularisation coinciding with increased leisure time, literacy, and availability of commercial printed texts during the Enlightenment. Early hits were texts like Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe in 1719. In the table below, I’ve highlighted some of the things that distinguish an epic poem from a novel.

| Epic poem | Novel |

| Partially divine protagonist (hero). | Fictional narrative of connected events, divided into chapters. |

| Great journeys and deeds, often related to the traditions of a people. | Written in prose. |

| Encounters with gods. | “Book-length”, from 50,000 to over 20,000 words depending on genre. |

| Stems from oral poetry. | Deals with the human experience, typically without the scope of an epic. |

| Uses traditional verbal formulas to aid memorisation. | Individualistic in nature compared to the epic. |

Comparative Mythology and the Flood Tablet

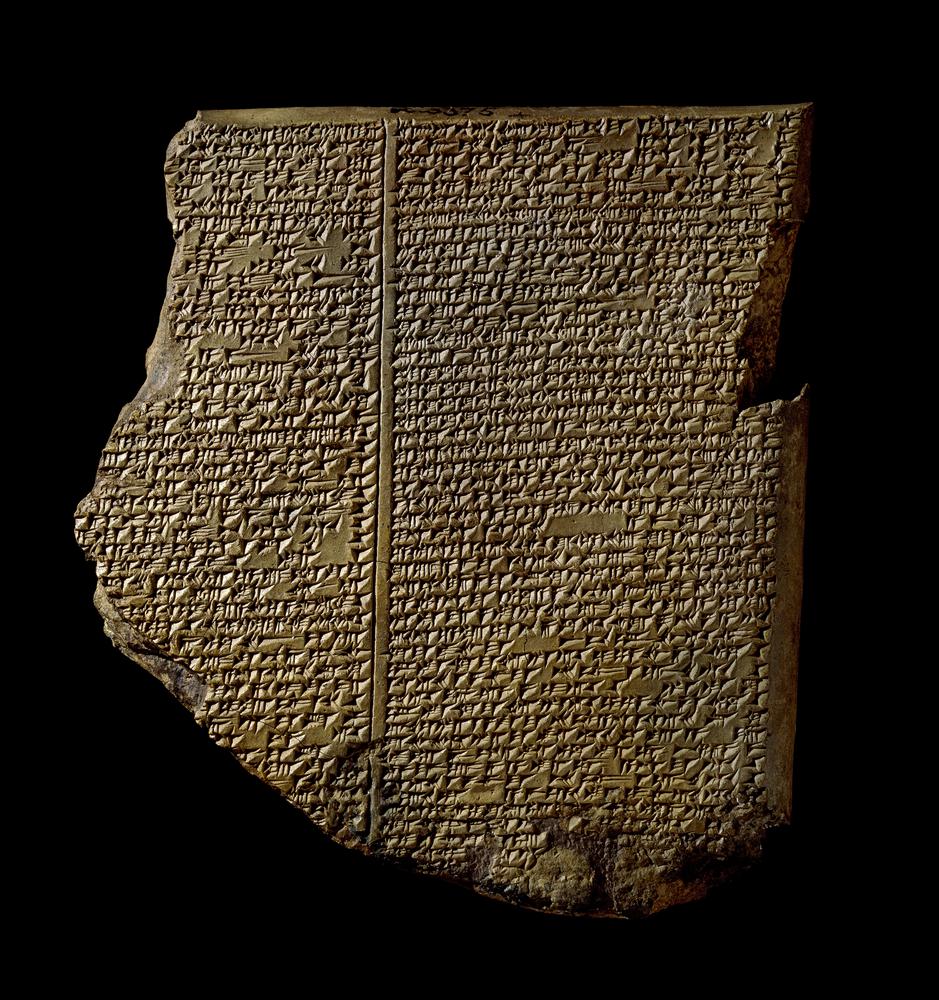

Allow me to introduce Tablet XI: the infamous Flood Tablet. It is, of course, in the British Museum, because what culturally significant artifact hasn’t been plundered by the Brits?

Tablet XI, The Flood Tablet, 7th century BCE, The British Museum.

Tablet XI caused a sensation when it was first translated in the 19th century. Have a look at the table below. It lists key narrative points from the Epic of Gilgamesh, as captured on tablet XI. Let me know if it starts to sound familiar.

| The Flood Narrative | ||

| 1. God/gods decide that mankind has become a pest. | 4. The man is ordered by god/gods to build an ark. | 7. The hero sacrifices an animal. |

| 2. God/gods decide to send a flood. | 5. The ark is loaded with breeding pairs of all animals. | 8. God/gods are pleased with the sacrifice. |

| 3. A single, worthy man is chosen to survive. | 6. The hero sends messenger birds to look for land. | 9. God/gods reassess their actions and will not repeat. |

The exact same narrative points are present in the Book of Genesis. The biblical hero, Noah, repeats these points step by step. Considering that the book of Genesis is dated around 3-5th century BCE, you can see why this discovery caused a stir. The Gilgamesh Flood Tablet predates Genesis by several centuries. In fact, there is evidence that the origin of this flood narrative lies much earlier than that.

So what does it mean? Yes, Mesopotamia had a lot of flooding. The resonance of a flood narrative and its associated symbolism of death and rebirth can be explained. But the strange entanglement of different flood narratives and their cultural significance are much more mysterious. In Gilgamesh, the gods are at times blood-thirsty, loving, cowardly, and generous. In Genesis, god may be wrathful and merciful at intervals, but he is always right. The Genesis narrative depicts essentially the same events, and yet the conclusion is a benevolent promise and a blessing for all posterity. Whereas the hero Gilgamesh, upon being told the story of the flood, is disappointed. The flood story is told to Gilgamesh precisely to extinguish his hope that he will be chosen and blessed with eternal life.

This is essential. The way we interpret these two texts, Gilgamesh and Genesis, couldn’t be more different. The contemporary Christian interpretation of the flood narrative is one of hope and protection. If you read Gilgamesh, the conclusion is much bleaker.

Why Do We Die?

The emotional core of the Gilgamesh narrative is grief. Midway through his adventures Gilgamesh loses his friend; his other self; the man who was literally created in opposition to him. Enkidu dies and leaves Gilgamesh bereft. What’s more, the king of Uruk begins to consider his own fate. The remainder of his story is a supernatural quest. Frightened by what has happened to Enkidu, Gilgamesh attempts – and ultimately fails – to secure immortality.

His struggles brought to mind another text I was reading around the same time. In his Confessions, Augustine of Hippo writes of the premature death of his closest friend. The language he uses is strikingly similar to that of Gilgamesh.

For I wondered that others, subject to death, did live, since he whom I loved, as if he should never die, was dead; and I wondered yet more that myself, who was to him a second self, could live, he being dead. Well said one of his friend, “Thou half of my soul”; for I felt that my soul and his soul were “one soul in two bodies”: and therefore was my life a horror to me, because I would not live halved. And therefore perchance I feared to die, lest he whom I had much loved should die wholly.

Augustine of Hippo, Confessions, AD 400.

As befitting the man who would later be declared a saint, Augustine ultimately chooses the Christian solution. He lets go of mortal things. Instead of holding on to grief, he decides to only love the immortal, i.e. god, through his creations. This takes the sting out of grief, because mortals are a mere sign of the eternal. But this option isn’t available to Gilgamesh. His gods are too human. They cannot be loved in this way. When he is finally thwarted in his goal to achieve eternal life, he has irrevocably lost his other half, and knows that his own mortal self must also be lost to death. What does Gilgamesh do then?

He builds walls. The only escape from death offered by the text is through great works, the likes of which will be told and retold through stories, for generations to come. If he was ever a real man, aspiring to such lasting fame, he has achieved his goal many times over, even after the fall of the walls of legend. Whether that fame provides consolation for grief over a loved one, or the inevitability of our own deaths, is for us all to decide.

Note: I read The Epic of Gilgamesh: An English Version with an Introduction by N. K. Sandars. This, however, was my undergraduate Penguin Classics purchase, so there may be better versions out there with more up-to-date scholarship!