Is your life online a net positive or not?

Is your life online a net positive or not?

Take a moment to breathe deeply in and out. Feel the air flowing through your lungs, cool or warm, light or heavy. Realize that each breath connects you to everything that lives: people, animals, plants, the wind, even the waves of the sea. Every inhale and exhale is an encounter with something else, something larger than yourself. Air is a shared space, yet an unequal one: some beings are suffocated by pollution, by cities, by industry; others claim the space and leave traces in the atmosphere.

At The Politics of Breath, that Studium Generale is organizing on February 10th at the Library, this shared breath takes center stage. It invites us to see air not as a neutral backdrop, an empty canvas onto which humans project their lives, but as something living. Air connects, influences, and shapes. It is a network in which human and non-human actors continuously interact. The wind, birds, trees, waves, microbes, and ourselves: we breathe and are part of a rhythm that exceeds our individual existence. In this context, the event invites us to step away from the idea that humans are the center of creation. We are not absolute rulers, but links in a complex network of bodies, rhythms, and movements.

To make these insights tangible, we are organizing a special evening in which we explore and experience shared breath. Together, we will examine how air, wind, and breathing connect us with everything that lives. We will look, listen, and feel what it means to be part of this network, and how art and technology can help make these connections visible.

One of the most fascinating guests of the evening is a so-called Strandbeest by artist Theo Jansen. These mechanical creatures live entirely on wind energy and move independently across the beach. They may seem simple, but they are both artwork and living laboratory: they breathe the wind, respond to their environment, and demonstrate how technology can help us reconnect with the world around us.

One of these strandbeests is actually a guest – and we will let it speak with the help of AI. We are invited to listen to air, space, and movement from a truly different perspective – one that is non-human, yet demands our attention.

The strandbeest reminds us that breathing is not only a biological act, but also a political and relational one. Whoever breathes affects and is affected. Air can be polluted and controlled, but it can also be shared, it can connect, and it can give us a different kind of insight: that we are never separate from the world, but always part of a larger network of living and moving forces.

This is why Politics of Breath is such an important theme. If we truly want the planet to have space for every living being — human and non-human — we need to look at what connects us. We need to learn to listen to the rhythms of the wind, the breath of plants, the whisper of the sea. Technology can help make these connections visible and tangible, rather than just dividing them. And we need to learn that breathing, co-existing, and sharing are not automatic — they are exercises, sometimes even political acts, and invitations to imagination.

Breathe deeply. Feel the air flowing through you. Realize that you are part of a living network. What does that mean? How does it affect you? Share your thoughts during the event.

Tuesday February 10, 17:00 – 19:00, TU Delft Library Central Hall

Free, register here

On Wednesday January 21st Studium Generale TU Delft celebrates its 80th anniversary. That’s 80 years of expanding academic horizons, critical thinking and social awareness, 80 years of lectures, debates, workshops and film screenings. Click here for the upcoming Spring Programme. We hope to welcome you at our events! When you are studying in the Library on January 21st please grab a piece of brainfood and good luck on your exams!

Team SG: Aga, Brigitte, Klaas Pieter, Leon, Lester, Marieke, Samanta, Sanne, Yolanda and Zuzanna

You wake up. Even before getting out of bed, you check your phone. One message, a notification, a headline. Something urgent. Something demanding attention. Something that makes you angry. Your brain immediately switches on.

On the way to work, you listen to a podcast “to stay updated.” At the office, you alternate between emails and tracking projects on a tool like Teams; you glance at news alerts and subtle reminders that your performance is measurable. By the end of the day, you feel tired, but also restless: have you done enough, learned enough, optimized enough? This is not personal weakness.

This is neurocapitalism.

Neuro…what…?!

Neurocapitalism is a term explored by artist and theorist Warren Neidich, who will give a lecture on January 27, 5:30 pm at the Faculty of Architecture in collaboration with Studium Generale TU Delft and BK Public Program. It describes how powerful platforms, tech companies, and even governments actively steer how we think, feel, and react. Our attention, emotions, and choices become raw material to be exploited for profit, influence, or social control. Especially today, as tech companies gain increasing political power, this poses a threat to autonomy and freedom – the principles at the core of democratic societies since the Enlightenment.

Neidich sees room for resistance. Neurocapitalism relies on the assumption of a fixed, predictable brain – but the brain can function differently, experience differently, and learn differently.

Neidich uses the concept of a brain without organs. It may sound strange – a brain needs organs to function – but the idea is philosophical, not literal. The brain is not a machine; depending on ideas and experiences, new patterns can emerge. It is partially plastic, meaning it can adapt to what is needed at a given moment.

A brain without organs describes a brain that allows wandering, boredom, doubt, play, and care – qualities that neurocapitalist systems often deem inefficient, yet which form a counterforce. Our brains are shaped by use, environment, and culture. According to Neidich, they are influenced by social structures, politics, technology, and cultural norms. Feeling constantly rushed is not an individual failure – it is a collectively programmed condition.

How does this work in practice? Our brains develop not only through genetics but also through interactions with tools, environments, and cultural practices. A child learning to write, an artist experimenting with new media, or your own cognitive habits shaped by smartphones – all create new possibilities for thought and perception.

Neidich uses a term of the French philosopher Bernard Stiegler: exosomatic organogenesis – literally, “organ formation outside the body.” It means that tools, technologies, and cultural practices shape and expand brain functions. New environments, art forms, or technologies allow the brain to form connections and learn in ways it could not before.

What if we deliberately redirect our cognitive capacities toward imagination and connection? Through art, stories, rituals, and philosophy, we create space to dream, experiment, and imagine new forms of collective life. Technology can enhance this: sensors, AI, and interfaces could help us “listen” to other forms of life, expanding perception, imagination, and empathy.

This is a direct strategy against neurocapitalism. Where capitalism isolates us, reducing our brains to measurable output and exploiting attention, a posthuman perspective connects us: with other Earthly beings, ecological networks, and knowledge systems often excluded from economic discourse. A brain that opens to these connections cannot be fully controlled by algorithms or platforms. It becomes a tool for critical thinking, creativity, and collective imagination – a way to reclaim autonomy and build a different relationship to the world.

With these ideas, Studium Generale TU Delft and students will collaborate at the For Love of the World festival on March 21, themed Digital Revolt. Guided by Warren Neidich’s theories and other thinkers, they will explore how art, technology, and imagination can converge to create a critical, creative installation. The project will not only explore the brain, but also how we relate to one another, to other forms of life, and to the planet itself. Out of love for the world—and as a counterforce against the power of neurocapitalism.

Neurocapitalism: Exploitation of our cognitive and emotional capacities by platforms, companies, or governments for profit or control.

Brain Without Organs: A brain that is open, flexible, and experimental—capable of wandering, play, and care, not just productivity.

Plasticity: The brain’s ability to change and adapt based on experience, environment, and culture.

Socio-political-technical-cultural plasticity: How brains are shaped not only biologically, but also by social structures, politics, technology, and culture.

Exosomatic Organogenesis: “Organ formation outside the body”; the idea that tools, technology, and cultural practices shape and extend brain development.

Posthuman perspective: Seeing humans as interconnected with other life forms and ecological networks, often via technology, expanding perception, empathy, and imagination beyond an exclusively human-centered worldview.

Are you an artist or poet connected to the TU Delft? Our next edition of the For Love of the World festival on March 21st 2026 will host an art exhibition and poetry reading by the community. This is an opportunity to share your work with a broad audience and maybe even sell a piece!

OPEN CALL FOR ARTISTS AND POETS

We are looking for art and poems for an exhibition at For Love of the World festival happening in March in Delft. This year’s theme is Digital Revolt💿, providing a platform for examining the powers and potential for love and connection in our digital lives. Find out more about the theme here.

All art is welcome! Whether you are amateur, professional, hobbyist, doodler, or fridge art gallerists we will provide space for you to share your art.

More information in the submission form.

Are you fascinated by the intersection of technology, art and philosophy? Do you want to help shape a world where digital technology fosters connection, imagination, and care, rather than control?

Studium Generale TU Delft is looking for two motivated student assistants to collaborate with internationally renowned artist Warren Neidich on a new art installation for the festival For Love of the World: Digital Love on 21 March 2026.

Digital Love is part of Warren Neidich’s long-term project Cognitive Architecture 2: From Noo-politics to Neuro-politics, which explores how architecture, artificial intelligence, and the human brain interact in the age of “neural capitalism.” In a world where algorithms shape perception, buildings adapt to our moods, and emotions circulate through social media and smart devices, Digital Love asks how the same systems that capture our attention might also open new possibilities for awareness, solidarity, and justice.

Against the backdrop of a capitalist order that exhausts the mind and turns thought into profit — from attention metrics and surveillance architectures to “smart” urban planning that predicts our behavior — the project seeks to reclaim the technological and architectural links between brain and world as spaces for empathy, play, and imagination. It gestures toward interactive spaces that invite reflection rather than reaction, and physical encounters — in galleries, streets, or shared digital rooms — that restore intimacy, care, and the capacity to dream together.

As a student assistant, you will support concept development and the realization of a physical or hybrid installation for the festival. You will contribute to content, form, and presentation, and assist with project organization alongside the SG team, the artist, and external partners. There is a renumeration for this position.

About the festival

For Love of the World: Digital Love explores love and intelligence in the digital age – between people, humans and machines, and between data and the Earth. Part laboratory, part temple, part playground, the festival invites participants to inhabit digital spaces anew: not as zones of fear and control, but as spaces for connection, attention, and hope.

About Studium Generale TU Delft

Studium Generale (SG) organizes lectures, debates, performances, workshops and festivals where science, art, and society meet. SG creates space for reflection, imagination, and dialogue at TU Delft – exploring what it means to be human (or more-than-human) in our time.

Interested?

Send your CV and a short motivation (max. 300 words) to Leon Heuts, Head of Studium Generale, at studiumgenerale@tudelft.nl before December 8.

Photo: Olivia Fougeirol

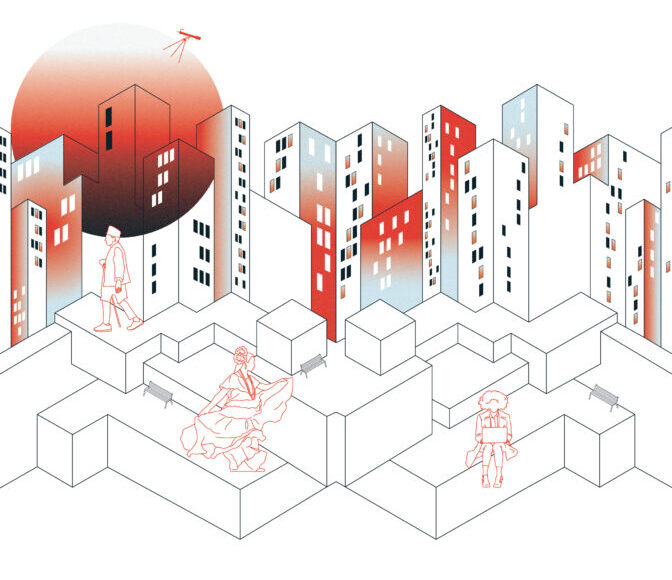

When we talk about public space, we usually think of squares, parks, and streets – places where people meet, move, protest, or rest. But public space is always political: it shapes who is visible, who can speak, and who is heard. Some people are given a voice, others ignored.

If we take a broader view, there is a much larger group that hardly has a voice: the non-human. Trees, birds, insects, fungi, rivers, even microbes in the soil exist in our cities and landscapes, yet we plan and build as if they do not matter – at most as decoration, or for economic utility. This is a perspective we can no longer afford.

In an era when nature returns like a boomerang – extreme weather, heatwaves, droughts, and floods are no longer abstract warnings but concrete consequences of ignoring life around us – it becomes clear that public space can no longer be exclusively human. Giving space to exist, human and non-human alike, strengthens the ecological resilience of our cities.

Sometimes it feels as if the Earth itself archives our mistakes. A dead albatross on a remote Pacific island, its stomach full of colorful plastic caps. A lake in Siberia whose sediment preserves radioactive isotopes, a legacy of nuclear tests. Microplastics now circle the globe as a new geological signature – a future fossil layer of ourselves.

We live in the Anthropocene, a time when humans have become a geological force. Such power brings responsibility. Physically, we accelerate entropy, the natural tendency of systems toward disorder. Life itself is a temporary slowing of that arrow of time, a local ordering that uses energy to create structure and relationships. And that works only in cooperation.

Evolution rarely hinges solely on survival of the fittest. Often it is survival of the connected. True, in nature animals sometimes try to kill one another: predators hunt, plants compete for light, bacteria fight for nutrients. But that struggle is only one layer of the story. Beneath it lies a deeper principle: cooperation, symbiosis, and mutual dependence. Mitochondria in our cells were once independent bacteria; they survived only by joining a host. Plant root networks share nutrients via fungi, bees pollinate flowers while gathering food, and microbes around our bodies cooperate to keep our digestion and immunity functioning.

It is this interconnection that makes life resilient, not brute struggle alone. Without cooperation and shared interests, ecosystems collapse, and no species – human or non-human – can maintain stable habitats. Connectedness is as evolutionarily successful, perhaps more so, than competition. Donna Haraway calls this “staying with the trouble”: learning to live with the complexity and vulnerability of the web we belong to, rather than pretending we can control it. Only by recognizing and nurturing relationships can we locally slow the arrow of time, curb chaos, and create space for life.

As the Japanese philosopher Kitarō Nishida wrote: “Space is not where things exist, but where relationships arise.” Taking this seriously transforms our orientation: space is not merely somewhere to move through, but a network of relationships. A city that gives space to the non-human is not only ecologically resilient but transforms how we perceive and act. Breathing, photosynthesis, nutrient cycles – every life-sustaining process connects us directly with other species and systems. Sharing space and listening to non-human signals lets us experience the interconnection of life.

This awareness evokes ethical values such as care for other living beings, reciprocity with ecosystems, a deep responsibility for resilient networks, and the appreciation of otherness — the recognition that other species and systems have intrinsic value, precisely through their connection to us. It also cultivates existential values: attention to the complex web we inhabit, humility in our ambitions, and connectedness as a guide for action. Human culture, science, and technology are not autonomous powers but ways to participate in a larger web. Our actions shape the ecosystem, and we are shaped by it.

This concept of shared space becomes tangible at the upcoming event in the Library Hall, where philosopher Sophie van Balen and a strandbeest by Theo Jansen will allow us to experience what it truly means to share air, life, and Earth. Join us, in thinking and creating a truly inclusive world.

In recent weeks, Studium Generale explored the theme of (re)claiming space – both literally and figuratively. What does it mean to claim space within the university, or in the city? Who decides who may stand where, speak, or remain silent?

Our first gathering focused on student protests on campus. Students entered into conversation with, among others, the director of the university library: does a demonstration belong within the institution of the university? If we see the university as more than a place of education and research – as a place of formation, of Bildung – then perhaps it should. Yet the tension remained palpable, though in a constructive way. One student said: “We oppose the course of the university itself. That can never be part of the institution.” Where does the space for dialogue end, and where does resistance begin?

These discussions on protest, participation, and institutional boundaries naturally led to questions about the deeper conditions for real change. This was the focus of our second event at Theater De Veste, together with the student association Argus from the Faculty of Architecture. The session carried the somewhat provocative title Woke Design, signaling a plea for inclusivity. There, we worked with a line of power: with each question about gender, education, or background, participants took a step forward or backward. A landscape of privilege emerged, in which men visibly stood at the front. It was confronting, but also enlightening. Beyond the exercise itself, the conversations made clear that genuine public space requires shared underlying values: without a commitment to inclusion and recognition, attempts at change remain superficial. Once again, something rare happened – real encounters between people who would normally never speak to each other: students and citizens of Delft, young and old.

(Re)claiming space thus turned out to be about more than occupying ground or raising one’s voice. It is about shaping a shared field of presence – one that requires attention, openness, and imagination. As Hannah Arendt observed, the public realm exists only “where people appear to one another.” But in our current and future-oriented work, we are stretching that insight further. How do we give space and voice to non-humans – animals, plants, rivers, or even AI? How do we account for the needs of future generations? Drawing on Donna Haraway, we begin to see the public as a multispecies space, where responsibility, care, and dialogue extend beyond the human. In this light, space is not a fixed given, but an act – a continual negotiation between self and other, even if the other is not human, and between the world as it is and the world as we collectively hope it might become.

Explore SG’s related events this quarter on the theme: (Re)Claiming Space

Men of the TU Delft, come make your voices heard on the problem of femicide and violence against women. Feel overwhelmed or powerless? That’s okay, but don’t be discouraged! There’s things you can do, and we’re asking you to do them. Yes – even if that means being emotionally vulnerable.

This Thursday, there’s a currents events lunch happening at 12:45 – 13:30 in the Library’s Orange Room. And we want you there.

A Current Event?

Putting the call to action for the men aside – it makes sense that a Studium Generale at a Dutch university would organise a discussion on femicide. It is our job to invite you to reflect on current events. But is femicide even a current event? In the Netherlands, a woman is murdered every eight days. You could argue that it is not the murders that took place this summer that make it a current event, but the protests that followed.

In my view, to call violence against women a “current event” actually misrepresents the nature of the problem. It is a part of the fabric of our society. In this article, I want to lay some groundwork for the conversation this Thursday. What is the problem, exactly? Why is it so hard to address? And above all: why do I think this conversation happening on Thursday is going to be so important?

Before we get into it, let’s have a look at some definitions.

Not Just Stranger Danger

Sexual violence is incredibly common. Nearly three-quarters (73%) of all Dutch women have been sexually harassed at some point in their lives. For only 19% of female victims of sexual violence, the perpetrator is unknown. We know that this isn’t just about “stranger danger” or staying safe at night. Similarly, in 56% of cases of femicide, the perpetrator is the woman’s (ex-)partner. I would go as far to say that the threat of (sexual) violence is embedded in the female experience.

Protests and Politicians

The protests and the varying responses from our politicians show the complex interplay between violence against women, questions of (Dutch) identity, women’s rights to safety and freedom, and harmful cultural conceptions of masculinity. Just look at the wide spread of solutions being championed. GroenLinks politician Mariëlle Vavier called for men to take responsibility and hold each other accountable for harmful behaviour. On the other side of the political spectrum, there are calls to increase police surveillance and curb immigration. The conversation is happening online and on our streets, ranging from marches and riots to Facebook Groups.

I’m laying this out so that we can realise how complex and pervasive the problem is. The politicisation of the issue brings attention, yes, but it also muddies the waters when it comes to causes and potential solutions. I’ll give an example. It struck me that the influence of substance abuse on intimate violence has not been a substantial part of the public discussion – except perhaps to victim blame. In 31 percent of instances of sexual violence against women, alcohol or drugs were involved. This may be cynical of me, but I can’t help thinking that with elections coming up, asking men to practice moderation is not a sexy campaign slogan. Nor is investing in addiction care – unfortunately.

So, uh, Why Am I Asking TU Men to Come Have This Conversation?

Our colleagues at the University of Utrecht came at this topic from the angle of how women can adapt and claim more space. After talking to their moderator, one of their programme makers wondered why they were focusing on women. Well, in Delft, we want to focus on men.

TU Delft has a gender ratio of 68% male to 32% female. Our students go out, form friendship groups, and shape who they are through new experiences and relationships. What better place to talk about male culture and behaviour? And no, we’re not planning to put all the weight of this terrible problem on your shoulders. We invited Hessel from Emancipator to talk with you about what it is like to navigate the world as a man, as a student, and in all the different roles you occupy as you go through life. Do you see opportunities to create a positive impact? Are there ways you can support others, and receive support? It’s going to be an exploration. With sandwiches. We hope to see you there.

We’ve all seen it: in a group, a few voices dominate, others fall silent, and some struggle to break through. Maybe you’re an introvert, like me? Personality plays a role — but so do identity, power, and context. What does it take for you to speak up and be heard?

Tomorrow at the TUD Library we’ll be asking: how do we express ourselves in public? Because what happens in small groups also plays out at the scale of society. We all want to be heard, seen, and included. But who gets space in public — both among peers and among opponents — is deeply political. And the spaces where we speak, online or in person, shape what is possible to say, and to whom.

Here’s the hard truth: expressing yourself is risky. You make yourself vulnerable to disagreement, criticism, even censorship or oppression. But speech can also be risky for others: words can wound, incite, or escalate into violence. The violent protest in The Hague last weekend is a stark reminder of what happens when emotions overwhelm reason: fear grows, society feels less safe, and democracy itself weakens.

So I keep circling back to three questions:

My instinct is yes: in theory, there should be room for everyone’s opinion. Pro-Palestine demonstrators should be allowed to speak, as should pro-Israel voices. Anti-immigration groups must be free to gather, and Antifa must be free to counter them — peacefully. That’s democracy.

But making space for all voices without letting violence dominate or silence take over requires more than just tolerance. It demands effort, empathy, emotional maturity — even intentional design of our public spaces. This is true for our streets, our social media (and the companies behind them), and even a place like a university campus. Looking at Karl Popper, the philosopher, the paradox of tolerating the intolerant is one that should be at the forefront of our minds in this age.

Perfect equity and perfect safety may be impossible. But democracy depends on our willingness to keep trying — to create spaces where as many as possible can speak, and still be heard.

Join us tomorrow to reflect on how we can shape that fragile, necessary balance.

12:45pm | Existential Tuesday: How do you claim space?

5:00pm | Is the campus designed for protest?