Veni, vidi, vici, Julius Caesar exclaimed after a victorious battle—three words that have since encapsulated the essence of decisiveness. Since then, the triad has become a powerful principle: from the Holy Trinity and the Three Wise Men to The Lord of the Rings trilogy and the structure of a well-told story with a beginning, middle, and end. We experience the world in three dimensions, so it is no coincidence that a festival like For Love of the World embraces this number.

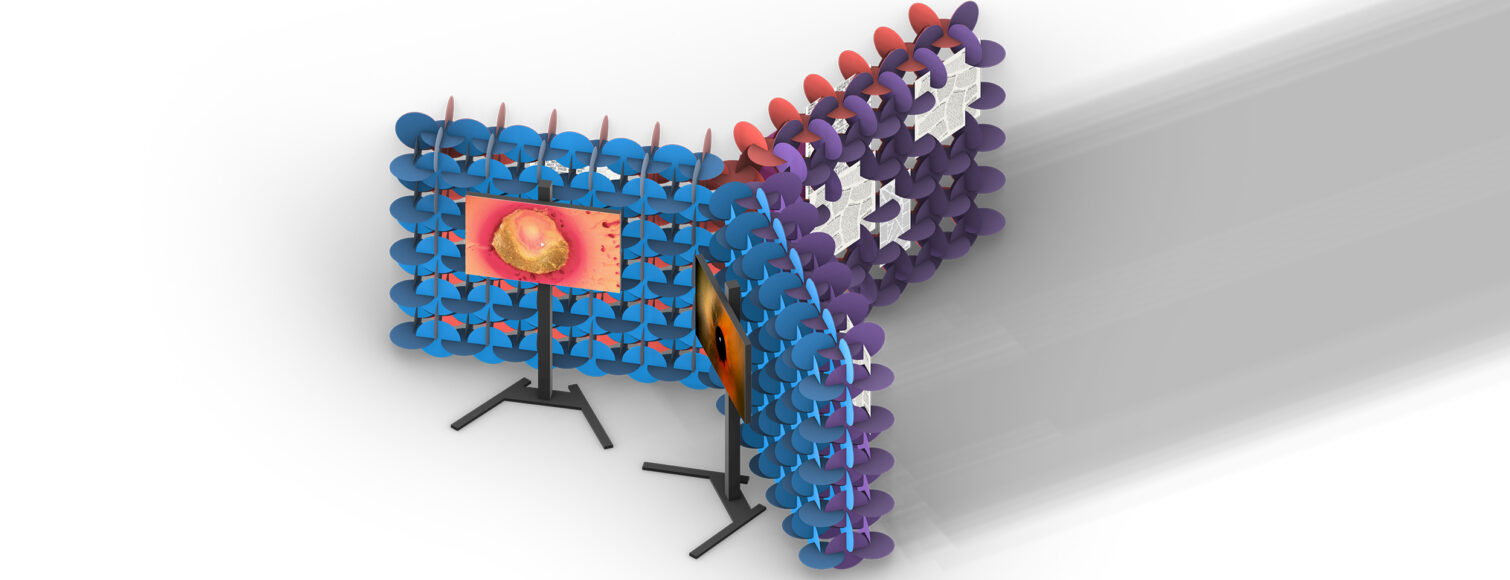

On March 29, an object will rise on the festival grounds that brings this triad to life: a horizontal Tripod. The structure is composed of approximately 800 cardboard rings, designed and built by students Tess Wilschut and Zuzanna Jastrzebska in collaboration with the architecture student association Argus. This construction extends in a Y-shape over nearly three meters and creates three zones. Each zone is dedicated to a fundamental dimension of human existence: our relationship with nature, society, and the divine.

This triad—nature, society, and the divine—is not just an abstract concept but reflects how we relate to each other and the world. Think of our centuries-old relationship with forests and oceans. They have been both a source of life and a threat. Forests provided food and shelter but also harboured wild animals and dangers. The seas provided fish and trade routes but also claimed countless lives through storms and shipwrecks. Societies began to organize and regulate nature. Forests were managed with rules on logging and hunting, while seas and rivers were divided into fishing grounds and trade routes. Both forests and oceans were not just physical spaces but also cultural and legal entities. Consider the sacred forests in various traditions or maritime law, which determined who was allowed to fish and sail where. At the same time, both forests and oceans have been places of contemplation and magic, as seen in ancient fairy tales and religious traditions. The sea symbolized the unknown, the boundary between worlds, a place of infinity and myth—from Norse legends of sea serpents to the spiritual significance of water in nearly all major religions.

But in modern times, this balance seems disrupted. Forests are reduced to suppliers of raw materials or carbon storage, while oceans are primarily seen as trade routes, tourist attractions, or industrial fishing zones.

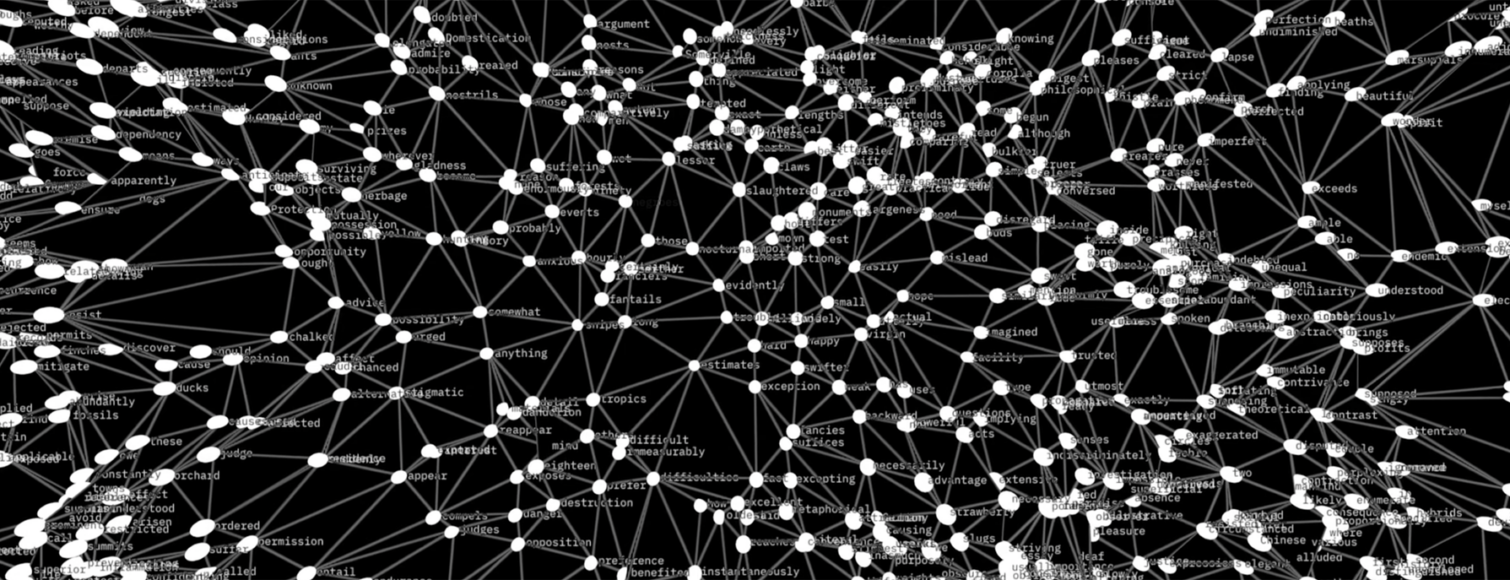

Traditionally, language has always been the key to how we understand the three dimensions—and thereby ourselves. We tell stories about nature, shape societies through laws, schools, science, and myths, and seek meaning through sacred texts. But the stories we tell have shifted solely to data and policy, while the dimension of society is increasingly derailed by polarization and the language of hate and war.

The dimensions seem to have turned against us. We face ecological crises. Living together—especially internationally—has become a precarious and dangerous matter. The divine, once a source of wonder and connection, is now used for exclusion and conflict, while leaders and states are worshipped with religious fanaticism, blind to facts and truth.

But if language has always been the key, could a new language reopen the way forward? The Tripod is an experiment in which we use large language models (LLMs) to explore this question. Critics fear that AI merely reproduces existing power structures and biases—sexism, racism, or the interests of the tech elite. But what if we can use LLMs to access these fundamental dimensions in a playful, anarchic way? So that they once again become part of a meaningful life, rather than being seen as something that threatens us?

See the Tripod as an improvised switchboard between you and nature, society, and the spiritual. In the ‘nature’ zone of the Y-shaped construction, you will find the stunning video installation NATURA by artist Floris Schönfeld. NATURA is an all-encompassing artificial super-intelligence that has managed to become one with the natural world in its entirety. TU Delft Researcher in human-robot relations Yke Bauke Eijsma will discuss AI as a new form of intelligence.

In the ‘society’ zone, you will encounter, among other things, the kilo-girls, which is a unit equal to the computational ability of 1000 women. Kilo-girls, created by artist Julia Luteijn, is a collection of computer-generated poems that reflect programmed biases. Prejudice, stereotyping, and discrimination are not confined to the human experience but are also inherited by the technologies we create. At the same time, in this zone, we see how technology can be used to be more inclusive and diverse, in collaboration with the Feminist Generative AI Lab from TU Delft and Erasmus University. In the spiritual section, we are working with researcher and futurist Gustavo Nogueira de Menezes on the Spiritual.AI chatbot.

These are small experiments, but with a serious background: can we use AI to breathe new life into the three dimensions, almost as a hack or a virus? What if AI is not just generative but also regenerative: inclusive, diverse, with room for the most unexpected stories? The Tripod is not a static entity, and we will certainly use it more often. But for now: come (veni) and see (vidi) if Zuzanna and Tess have managed to put the thing up (vici).

Leon Heuts, head of Studium Generale