Join us for an interactive panel discussion on the ethics of military and dual-use technology

on Tuesday May 13th at the TU Delft Library!

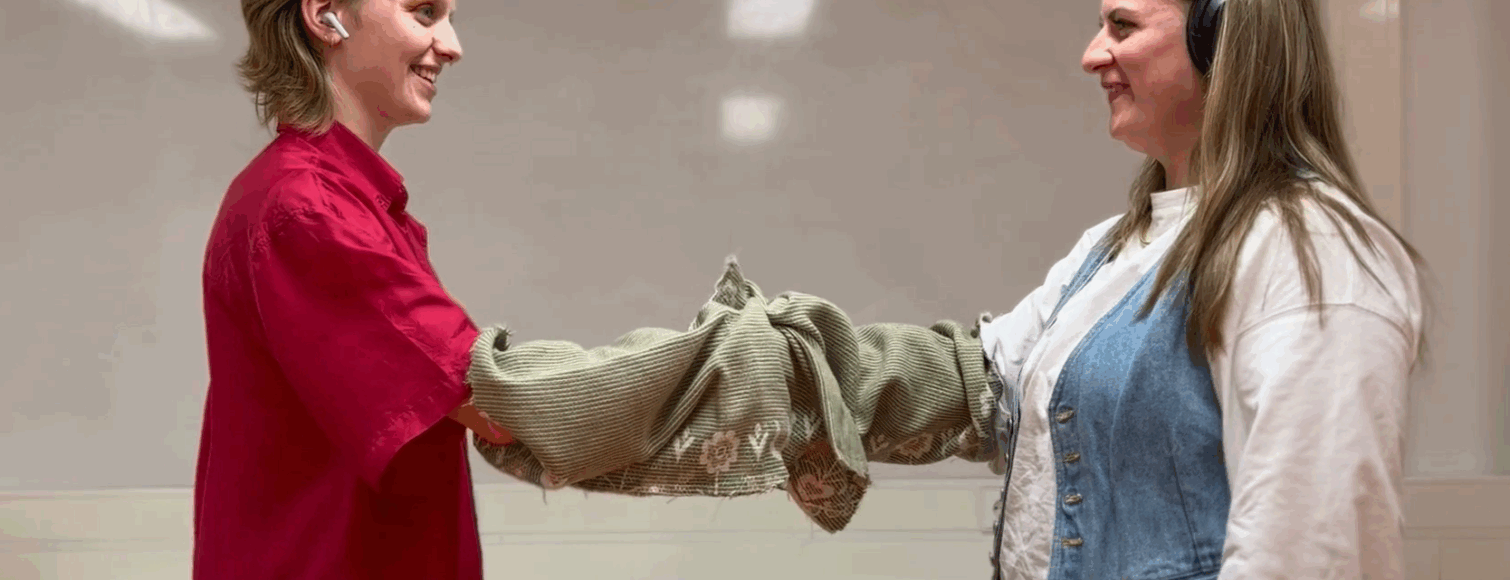

Centuries ago, Leonardo Da Vinci is said to have destroyed his schematics for a submarine, out of fear for how they may be used at war (Chalk 1989). His story is not unique. Scientists and engineers have long been troubled by the moral weight of their discoveries and creations. Is the world better for their work – that men may better kill one another? Albert Einstein both promoted and later protested the development of nuclear weapons. His letter, written with Leo Szilard in 1939 to then US president Franklin Delano Roosevelt helped spur the Manhattan Project into existence. Years later, in 1946 Einstein was warning the world against the danger of the very same weapons and their proliferation.

Today’s researchers struggle with many of the same questions. How might their work be used, for better or worse, in war? Google employees have protested their company’s involvement in the development of AI defense intelligence tools. Despite high profile protests like this, surveys in the United States found that a majority of AI professionals feel either positively (38%) or neutral (40%) about participating in research funded by the Department of Defense. Only a minority (24%) viewed such work negatively (Aiken 2020). Motivated variously by a sense of patriotism, civic duty, and or fear of war, many turn their technical skills to develop weapons. Young technical professionals can be seen in increasingly large numbers at hackathons and in the attendance at job fairs where defense companies recruit. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has motivated many to pursue careers in defense who may otherwise never have considered it. Indeed, it is precisely such technological innovativeness which has helped Ukraine defend itself in the face of overwhelming odds.

Here at TU Delft, similar questions prompt students and staff to question the future role of the university. For some, research in the military domain offers a promising way not only to secure funding, prestige, and intellectually fruitful partnerships, but also a way to respond to broader geopolitical fears. Concerns run high about the combined effect of Russian aggression and the manic American mix of saber-rattling and political side-switching. As the Netherlands considers for the first time in 27 years to reintroduce military conscription, the TU Delft wonders what its place in such a more militarized society could be. Indeed, the official statement from the TU Delft on why it collaborates with the defense industry cites Ukraine specifically, alongside the desire to rely less on other countries and “take more responsibility for defence, both within NATO and in the EU.” The duty and mission driven language of the statement ties its collaborations with the defense industry to TU Delft’s refrain ‘impact for a better society’.

Research of interest to defense is not restricted to those projects and partnerships which are explicitly dedicated to weapons systems (like the internships with Lockheed Martin to develop F-35s). Considering how many technologies are dual-use, innovation which may capture military attention happens in unexpected places. It was only as recently as mid-April that a team from TU Delft won a drone racing championship with autonomous drones against human competitors. It leaves little work to the imagination to see how such progress could also be put to use at war.

As momentum builds for deepening partnerships between military, private, and academic institutions, some protest. At the Delft Career Days in February, eleven activists were arrested for protesting (in addition to fossil fuel companies) the presence of companies involved in the development and production of weapons, and particularly those which sell arms to Israel. Meanwhile, in the past few weeks, the ‘Delft Student Intifada’ (DSI), distributed an informational package to professors across campus with the aim of ending collaborations with Israeli institutions. The material, available online includes a ‘complicity map’ documenting projects they argue are morally complicit in genocide.

At some level, a fair deal of what is argued for and against TU Delft’s partnerships with defense comes down to political affiliation. An emphasis on helping Ukraine is frequently used to justify support for defense partnerships. Solidarity with Palestine may predict greater skepticism. However, the deep commitments we have, even implicitly, to morality, science, and politics are more varied than such a simple and partisan characterization might indicate.

A more fundamental questions concerns what the university is and should be. The TU Delft official statement describes the university’s social mission, and the DSI website discusses the “soul” of the university. Over sixty years ago, Dwight D. Eisenhower described the transformation of scientific research in the United States brought about by federal funding and military investment:

“Today, the solitary inventor, tinkering in his shop, has been over shadowed by task forces of scientists in laboratories and testing fields. In the same fashion, the free university, historically the fountainhead of free ideas and scientific discovery, has experienced a revolution in the conduct of research. Partly because of the huge costs involved, a government contract becomes virtually a substitute for intellectual curiosity.”

In some sense, both TU Delft as well as activist anti-militarist movements are trying to articulate and balance the tensions between social obligations, scientific aspirations, and intellectual freedoms. The outcome of how they weigh these values against one another entails the very character of the university itself.

Like much good philosophy, the questions that underlie those debates are so basic as to typically be asked either only at the end of a very long, tiresome, and abstract conversation – or by a child. What sort of university is it that makes weapons? What responsibilities do scientists and engineers have for their creations? When is war just, can it ever be? Are some technologies inherently bad? What sort of person would you be, if you designed things which kill? Like any self-interested philosopher, I could emphasize how important each of these questions can be, how we ought to have more ethics classes and so on. The philosophers want funding too.

With all this talk about war and the ethics of weapons research we might lose sight of a simpler and often ignored question: What is peace? Often, peace is taken to be war’s opposite, an absence of violence. In a metaphor, peace might be seen like cold, the absence of heat. There are some who might accept this notion, that we have peace so long as the guns go silent. In that case, there are plenty of ugly and atrocious sorts of peace: slavery, submission, or the tolerance and tenuous truce of the time before the guns start up again, an interbellum.

For others, peace is positive, substantive, it has something to it more than the mere absence of war (Fiala 2023). So for those who may read this article and in response quote some old Latin, saying Si vis pacem, para bellum ‘If you want peace, prepare for war’ we are still stuck asking what it is we really want. If peace is positive, then we must also ask how to prepare ourselves. Are we prepared for peace, do we have the necessary tools, do we have the institutions, do we have the character? What more do we need? Beyond just truce and tolerance, if we were to have lasting peace, could we bear it?

The political sentiments which seem to motivate views on military research may well conceal deeper differences in what we conceive of as peace. If peace is simply war’s absence, then it is perhaps easier to justify the energy, creativity, and spending that goes towards preparation for war. If, however, peace is something more and we desperately lack it, even domestically, then demands to prepare for war so as to achieve peace are likely to require much more justification. So when we ask ourselves about the ethics of military research and defense partnerships, first find your vision of peace, and ask what we are and should be preparing for.

Recommended Reading:

Virgina Woolf, Three Guineas, 1938

Academic References:

Aiken, C., Kagan, R., & Page, M. (2020). ‘Cool Projects’ or ‘Expanding the Efficiency of the Murderous American War Machine?’. Center for Security and Emerging Technology. https://cset.georgetown.edu/publication/cool-projects-or-expanding-the-efficiency-of-the-murderous-american-war-machine/

Chalk, R. (1989). Drawing the Line: An Examination of Conscientious Objection in Science. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 577(1), 61–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1989.tb15050.x

Fiala, A. (2023). Pacifism. In E. N. Zalta & U. Nodelman (Eds.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2023 Edition). Stanford University. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2023/entries/pacifism/