You wake up. Even before getting out of bed, you check your phone. One message, a notification, a headline. Something urgent. Something demanding attention. Something that makes you angry. Your brain immediately switches on.

On the way to work, you listen to a podcast “to stay updated.” At the office, you alternate between emails and tracking projects on a tool like Teams; you glance at news alerts and subtle reminders that your performance is measurable. By the end of the day, you feel tired, but also restless: have you done enough, learned enough, optimized enough? This is not personal weakness.

This is neurocapitalism.

Neuro…what…?!

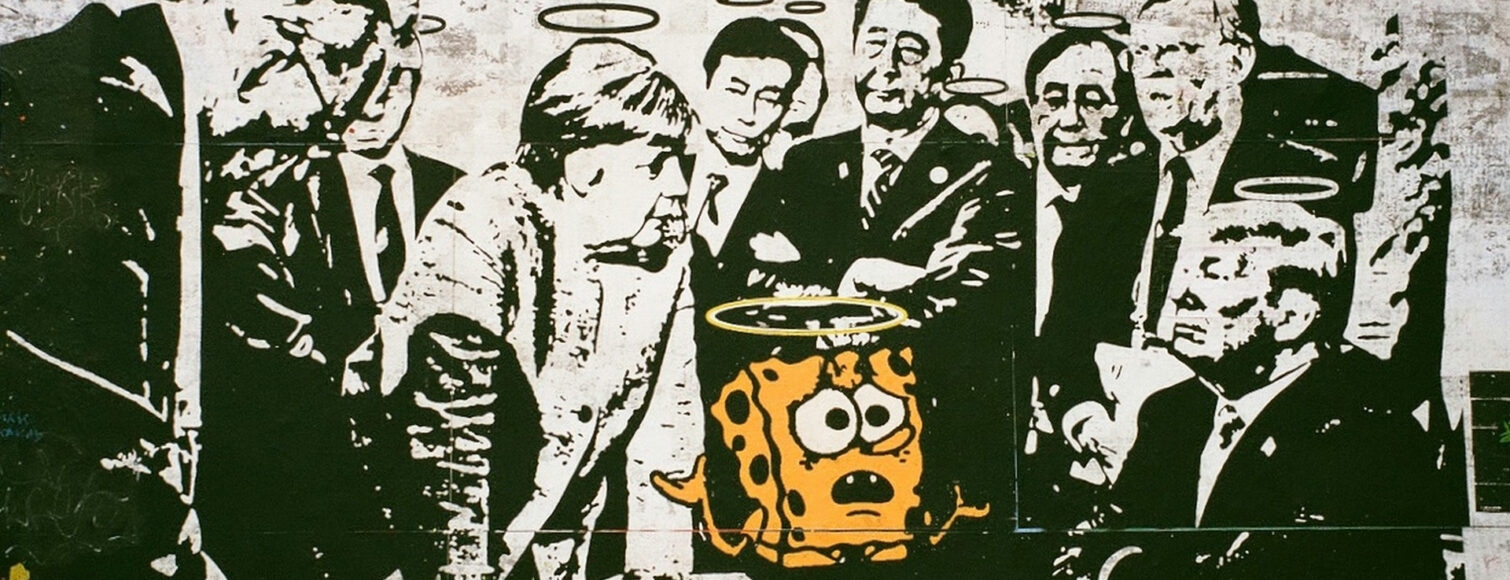

Neurocapitalism is a term explored by artist and theorist Warren Neidich, who will give a lecture on January 27, 5:30 pm at the Faculty of Architecture in collaboration with Studium Generale TU Delft and BK Public Program. It describes how powerful platforms, tech companies, and even governments actively steer how we think, feel, and react. Our attention, emotions, and choices become raw material to be exploited for profit, influence, or social control. Especially today, as tech companies gain increasing political power, this poses a threat to autonomy and freedom – the principles at the core of democratic societies since the Enlightenment.

Neidich sees room for resistance. Neurocapitalism relies on the assumption of a fixed, predictable brain – but the brain can function differently, experience differently, and learn differently.

Neidich uses the concept of a brain without organs. It may sound strange – a brain needs organs to function – but the idea is philosophical, not literal. The brain is not a machine; depending on ideas and experiences, new patterns can emerge. It is partially plastic, meaning it can adapt to what is needed at a given moment.

A brain without organs describes a brain that allows wandering, boredom, doubt, play, and care – qualities that neurocapitalist systems often deem inefficient, yet which form a counterforce. Our brains are shaped by use, environment, and culture. According to Neidich, they are influenced by social structures, politics, technology, and cultural norms. Feeling constantly rushed is not an individual failure – it is a collectively programmed condition.

How does this work in practice? Our brains develop not only through genetics but also through interactions with tools, environments, and cultural practices. A child learning to write, an artist experimenting with new media, or your own cognitive habits shaped by smartphones – all create new possibilities for thought and perception.

Neidich uses a term of the French philosopher Bernard Stiegler: exosomatic organogenesis – literally, “organ formation outside the body.” It means that tools, technologies, and cultural practices shape and expand brain functions. New environments, art forms, or technologies allow the brain to form connections and learn in ways it could not before.

What if we deliberately redirect our cognitive capacities toward imagination and connection? Through art, stories, rituals, and philosophy, we create space to dream, experiment, and imagine new forms of collective life. Technology can enhance this: sensors, AI, and interfaces could help us “listen” to other forms of life, expanding perception, imagination, and empathy.

This is a direct strategy against neurocapitalism. Where capitalism isolates us, reducing our brains to measurable output and exploiting attention, a posthuman perspective connects us: with other Earthly beings, ecological networks, and knowledge systems often excluded from economic discourse. A brain that opens to these connections cannot be fully controlled by algorithms or platforms. It becomes a tool for critical thinking, creativity, and collective imagination – a way to reclaim autonomy and build a different relationship to the world.

With these ideas, Studium Generale TU Delft and students will collaborate at the For Love of the World festival on March 21, themed Digital Revolt. Guided by Warren Neidich’s theories and other thinkers, they will explore how art, technology, and imagination can converge to create a critical, creative installation. The project will not only explore the brain, but also how we relate to one another, to other forms of life, and to the planet itself. Out of love for the world—and as a counterforce against the power of neurocapitalism.

Glossary of Key Terms

Neurocapitalism: Exploitation of our cognitive and emotional capacities by platforms, companies, or governments for profit or control.

Brain Without Organs: A brain that is open, flexible, and experimental—capable of wandering, play, and care, not just productivity.

Plasticity: The brain’s ability to change and adapt based on experience, environment, and culture.

Socio-political-technical-cultural plasticity: How brains are shaped not only biologically, but also by social structures, politics, technology, and culture.

Exosomatic Organogenesis: “Organ formation outside the body”; the idea that tools, technology, and cultural practices shape and extend brain development.

Posthuman perspective: Seeing humans as interconnected with other life forms and ecological networks, often via technology, expanding perception, empathy, and imagination beyond an exclusively human-centered worldview.