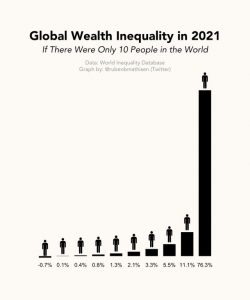

What’s really wrong with extreme wealth? Haven’t men—since it’s nearly always men—like Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos earned their fortune through hard work and smart business strategies? Who are we, the average people, to criticize them? Isn’t our disdain rooted in jealousy because we secretly wish to be like them?

It’s curious that we even ask such questions – questions which reflect the very liberal times we live in. We’ve become so accustomed to the idea that we are all the entrepreneurs of our own lives, responsible for our own success, that we often view the ultra-wealthy as simply exceptionally successful. We assume they’ve earned it, while the real damage that wealth disparity inflicts on society and the planet is often overlooked.

Yet, research shows that concentrated wealth is deeply harmful. Ingrid Robeyns, a professor of ethics at Utrecht University, makes this case in her book Limitarianism. Her argument for capping wealth is not ideological but practical: extreme wealth undermines societies by concentrating power in the hands of a few, enabling them to shape politics in their favor or threaten to withdraw their capital if policies don’t suit them.

Historically, philosophers like Rousseau and Marx warned against the dangers of such wealth concentration. They argued that personal wealth often conflicts with the common good. Rousseau famously suggested that the first person to claim land as “theirs” and convince others of it should have been cast out. Instead, we admired them.

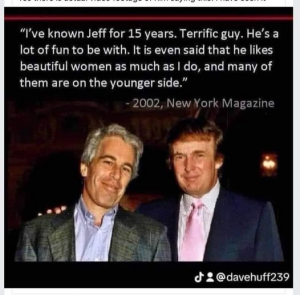

More importantly, these philosophers point out a more psychological danger. In today’s world, wealth has become a fetish, distorting our perception of what’s natural or deserved. Charismatic billionaires are celebrated as visionary heroes, even though their wealth is often built on exploitation, tax evasion, or pure luck. The real danger lies in how this wealth worship infiltrates society, convincing us that disruption and endless growth are virtues, when in reality, they often mask destructive power.

This glorification of extreme wealth creates a deeper cultural problem: we begin to idolize the “disruptors,” treating them as modern-day saviors. Figures like Elon Musk and Steve Jobs are portrayed as rebels and visionaries who single-handedly change the world. They embody a secular form of salvation, suggesting that anyone who works hard and breaks the rules can achieve the same success. As Apple’s famous slogan goes: “Here’s to the crazy ones, the misfits, the rebels…” But behind this image lies a more troubling reality.

Disruption, the ethos of these wealthy entrepreneurs, often transforms into destruction. Musk’s purchase of Twitter, for example, which turned the platform into a haven for conspiracy theories and misinformation, shows how “disruption” can spiral into chaos. The underlying message is clear: distrust the world as it exists and tear it down, regardless of the consequences. This echoes ancient Gnostic beliefs that the material world is inherently corrupt and salvation comes only by rejecting it.

It’s no coincidence that figures like Richard Branson and Elon Musk are involved in space exploration, or that Google’s offices resemble utopian environments, as parodied in Dave Eggers’ The Circle. The world is viewed as a chaotic, unreliable place that must be escaped—a place doomed to collapse. Musk, according to his biographer Ashlee Vance, is “consumed” by the idea that the apocalypse is near. He even speculates that our world is likely just a computer simulation, like in The Matrix.

This kind of world-denial is also reflected in how Steve Jobs’ charisma has been described as a “reality distortion field.” The term comes from a Star Trek episode where aliens on a barren planet could create new realities purely through mental power. Similarly, Jobs and Musk have a knack for bending reality to fit their vision, distancing themselves from ordinary life and creating idealized worlds of their own.

In this worldview, the existing reality is flawed and must be rejected or “disrupted.” This mindset fosters a detachment from real-world problems, replaced by fantasies of space colonization or digital utopias. Beneath this visionary allure is a dangerous tendency for the individual to abandon the current world and its pressing issues, reinforcing isolation and disconnection from the welfare of the collective.

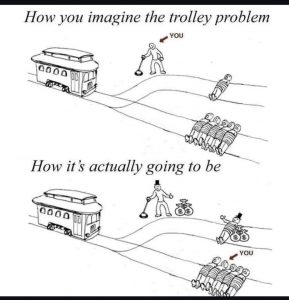

This mindset is dangerous not just because it separates the rich from society, but because it seeps into everyday culture. We begin to believe that we must also constantly “disrupt” ourselves to succeed. Flexibility, perpetual reinvention, and boundless creativity become the ideals, leaving workers stressed, precarious, and primed for exploitation. Creativity, once an avenue for challenging the status quo and pointing out societal flaws, has now been reduced to mere problem-solving.

The problem isn’t just the wealth itself, but the ideology that surrounds it—an ideology that glorifies wealth and power while ignoring the real costs to individuals and societies. The ultra-wealthy represent a particular culture or ideology that we’re all immersed in—like fish in water, unaware of the medium we swim in. How do we deal with this? Perhaps the first step is recognizing which “water” we are in. To what extent do we want to participate in this system? Can we make different choices regarding money or possessions?

But the central question remains: what do we do about the ultra-wealthy? History shows that revolutions can easily descend into their own form of religious madness. Perhaps Power and Privilege, a program from Studium Generale, offers a good starting point for exploring these issues. You might also consider attending Eat the Rich at Theater de Veste—a game and lecture in one—or watching the documentary series Exterminate All the Brutes at 38CC.

Leon Heuts, head of Studium Generale TU Delft